This content is available thanks to subscriber support. To subscribe to the full newsletter, see subscription options here or click the button above.

Carbon credits are two things: the mechanism that enables emitting industries to target net zero emissions and the market that encourages new carbon reduction or removal projects by giving value to carbon.

Carbon credits are a key part of the green transition as mandated by governments around the world. But the double whammy of recession risk stealing investment attention and a crisis of confidence in how carbon credits are certified hammered the voluntary carbon market in 2022.

It’s an opportunity.

In this month’s issue I explain what carbon credits are, the two kinds of carbon markets, why their prices diverged so much last year, and why now is a good time to start positioning. Of course, I also say what I’m buying to give my portfolio exposure to an essential cog in the green machine that is very undervalued today.

Carbon Credits 101

Taking concrete steps to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is not a choice but a requirement for corporations of all sizes around the world as per government mandates.

Companies first work to reduce direct emissions. But for most it is impossible to reduce their way to zero. All manner of businesses, from manufacturing to travel to health to energy and beyond, cannot avoid emitting…yet there’s all kinds of pressure, from government and consumers, to get to net zero.

Carbon credits bridge this gap.

The carbon market allows organizations to neutralize the GHGs they can’t help but emit by funding projects that avoid or reduce emissions from other sources or that remove GHGs from the atmosphere.

Carbon credit projects fall into two broad categories:

GHG avoidance or reduction projects, such as green energy (which avoids use of fossil fuels) and avoided deforestation

GHG removal or sequestration projects, such as reforestation and technology-based removal

Often these projects can also create other benefits, such as increased biodiversity, job creation, reduced duress, and health benefits from avoided pollution.

There are two carbon credit markets: compliance and voluntary. Compliance markets are geographic areas where regulators have put caps on emissions for each industry; companies that exceed their cap can trade for credits or pay a penalty (cap and trade). The largest compliance markets are the EU, UK, California, and the northeast US.

Voluntary carbon markets (VCM) are the emissions market for everyone else. Entities (companies, governments, individuals) can buy or produce carbon credits. The ability to monetize the ‘carbon value’ makes carbon projects happen, be it protecting a swath of rainforest, capturing livestock methane, or switching out dirty cookstoves for clean ones. And the ability to buy credits enables all companies to aim for net zero.

Since one is required and the other voluntary, there are differences between these two carbon markets that matter to investors.

In compliance markets, clear rules and caps created solid foundations to price carbon credits. In most jurisdictions, prices stayed within an initial range for years then moved up dramatically in 2021 when governments globally tightened carbon targets. Now those higher prices are the new range.

The voluntary market, by contrast, had no such pressure. Companies choose to participate, setting their own goals and buying credits to get there…or not. Participation ends up depending as much on the overall economy as on any desire to meet carbon goals. (I get into this in the next section).

Since motivation is far more pliable, pricing has been much more volatile. In 2022, carbon credits in the compliance market stayed relatively stable, holding those 2021 gains, but prices in the voluntary market fell 30 to 70%.

I’ll discuss what this means for interested investors later. First I must explain why the VCM market had such a rough year.

2022: A Rough Year for the VCM

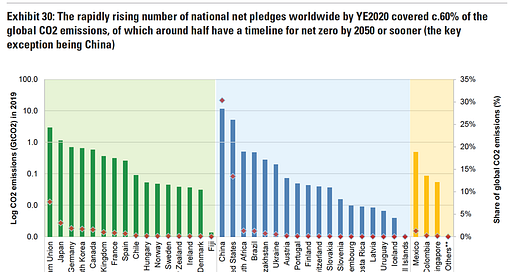

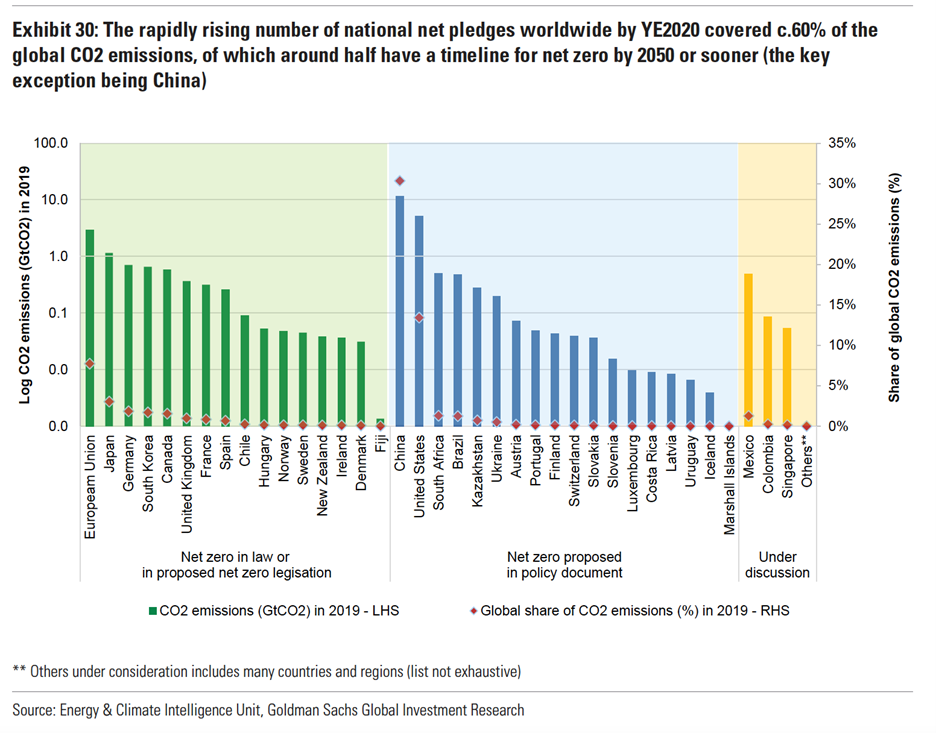

You probably haven’t heard the words ‘carbon credits’ much lately and so you might think the system is losing steam. But that is not the case. In fact, despite the Russia-sparked energy crisis, slowing growth, inflation concerns, and a significant stock market slide, there was continued action on climate change from government around the world in 2022. With several new instruments launched and some scope expansions, 23% of global GHG emissions are now covered by reduction mandates, up from 7% in 2013.

“This year’s report shows that governments are prioritizing direct carbon pricing policies to reduce emissions, even in difficult economic times.”

– State and Trends of Carbon Pricing, World Bank, May 2023

But despite all this growth, there are two reasons why carbon credits aren’t attracting much attention these days.

The first is macro: rate hikes and recession risk have pushed other ideas off the stage. And fair enough – when the core of economic well-being is at risk, few people are inclined to invest in economic growth, whether industrial or green.

Economic cycles impact paradigm shifts. Shifts accelerate when a humming economy and confident market send abundant money flowing to exciting new ideas. When the economy is bumbling along and investors are unsure, capital is constrained and investors gravitate to safer bets.

Today the news is all about Treasury yields and debt ceilings and inflation numbers and job openings. And AI is attracting the speculative money that is in the market. So green opportunities aren’t getting investor attention, which means many are capital constrained, which slows their progress and reinforces the cycle.

But this negative cycle will turn around because the green transition is not an idea or possibility. It is a mandated reality. So once recession risk ebbs (because we either have a recession or manage to establish good growth with low inflation) and investors start looking to the future again, green opportunities will rise to the top.

The second reason you haven’t heard enthusiasm about carbon credits lately is that the sector is managing some growing pains. It’s not surprising – rarely does a new and rapidly-growing industry avoid stumbles – but it is notable. For the VCM, the challenges are all about what having confidence that a carbon project does what it’s supposed to do.

The standout story is Verra, the US nonprofit that dominated carbon credit certification in the VCM. An investigation by The Guardian, Die Zeit, and SourceMaterial found Verra had certified many billions of dollars in carbon credits that were worthless. Key among those were credits bought by Disney, Shell, Gucci, and other big companies based on stopping destruction of rainforests that were never threatened.

The Verra story highlighted the challenges of the carbon credit system.

How are carbon credit projects established and certified?

Who monitors projects to assess continued compliance over the project’s lifespan?

How are the needs of local populations protected?

I’m simplifying a complex system, of course, but that’s the gist of it. There are major efforts well underway to answer these questions with new mechanisms that would standardize certification, monitoring, and impact assessment across the VCM.

Market-wide mechanisms had to happen. It kind of works well that these weaknesses came to the fore while investors were unlikely to be interested in the sector anyway, for all those macro reasons.

So that’s why you haven’t been hearing about carbon credits recently.

Now it’s time to explain why you will hear about them, a lot, over the next decade.

Growth Ahead

To limit global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees by 2050 requires, among other things, 2 GT of carbon sequestration and removal by 2030. To do that requires 15 times the voluntary carbon credits of that type that were available in 2020.

A 15-fold increase is big. But the VCM will grow much more than that because sequestration and removal are one side of the VCM. The other side is avoidance and reduction, credits for which will also grow as companies strive for net zero.

The VCM is currently valued at about $1.5 billion (2022 is not shown on the chart below). The market jumped in value in 2021 as the post-COVID stock market soared and government reinforced emissions mandates.

Then, as I said, the market stepped back as stocks slid, certification challenges hit the VCM, and money got tighter.

I don’t expect carbon prices to turn upward sharply soon. But the downtrend will end once we exit this uncertain macroeconomic limbo. And when we do, the VCM will have to grow dramatically to meet the GHG needs that governments around the world have set.

From $1.5 billion, the VCM could reach anywhere from $5 billion to $50 billion by the end of 2030 according to the International Emissions Trading Association’s latest report. Others have even higher estimates.

This content is available thanks to subscriber support. To subscribe to the full newsletter, see subscription options here or click the button above.